MnZn Ferrite Core: Properties, Applications & Selection Guide

What Makes MnZn Ferrite Cores Essential for Modern Electronics

MnZn ferrite core is soft magnetic ceramic materials composed of manganese (Mn), zinc (Zn), and iron oxide (Fe₂O₃), offering exceptional performance in frequencies ranging from 10 kHz to 1 MHz. These cores dominate power supply transformers, EMI suppression components, and inductive applications due to their high permeability (typically 2,000-15,000), low core losses, and cost-effectiveness compared to other magnetic materials.

The primary advantage lies in their superior magnetic properties at low to medium frequencies. Unlike NiZn ferrites which excel above 1 MHz, MnZn ferrites achieve maximum efficiency in switch-mode power supplies, DC-DC converters, and common-mode chokes where frequencies remain below the megahertz range. Their electrical resistivity of 1-10 Ω·m minimizes eddy current losses, making them indispensable for energy-efficient electronic designs.

Magnetic Properties and Performance Characteristics

Initial Permeability and Frequency Response

The initial permeability (μi) of MnZn ferrite cores varies significantly based on material composition and manufacturing processes. Standard grades exhibit permeabilities between 2,000 and 5,000, while high-permeability variants reach 10,000 to 15,000. This parameter directly influences inductance values and determines the core's suitability for specific applications.

Frequency characteristics show distinct behavior patterns. Below 100 kHz, MnZn ferrites maintain stable permeability with minimal losses. As frequency increases toward 1 MHz, permeability decreases while core losses rise due to magnetic relaxation phenomena. Material grades are engineered for specific frequency windows—power ferrites optimize for 20-200 kHz, while broadband types extend usable range to 500 kHz.

Core Loss Mechanisms

Total core loss comprises three components: hysteresis loss, eddy current loss, and residual loss. In MnZn ferrites operating at typical frequencies, hysteresis loss dominates below 100 kHz, while eddy currents become significant above 200 kHz despite the material's high resistivity. Modern low-loss grades achieve power loss densities below 300 kW/m³ at 100 kHz and 200 mT, crucial for high-efficiency power converters.

| Material Grade | Initial Permeability (μi) | Saturation Flux (Bs) mT | Optimal Frequency Range | Core Loss (100kHz, 200mT) kW/m³ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Power Ferrite | 2,300 | 470 | 25-200 kHz | 220 |

| High Permeability | 10,000 | 380 | 10-100 kHz | 350 |

| Low Loss | 3,000 | 490 | 50-500 kHz | 180 |

| Wide Band | 2,500 | 450 | 100 kHz-1 MHz | 280 |

Temperature Stability

MnZn ferrites exhibit temperature-dependent magnetic behavior with Curie temperatures typically ranging from 180°C to 250°C. Permeability increases with temperature up to the Curie point, where magnetic properties disappear completely. Operating temperatures should remain below 120-140°C for most applications to maintain stable performance and prevent permanent degradation.

Core Geometries and Design Considerations

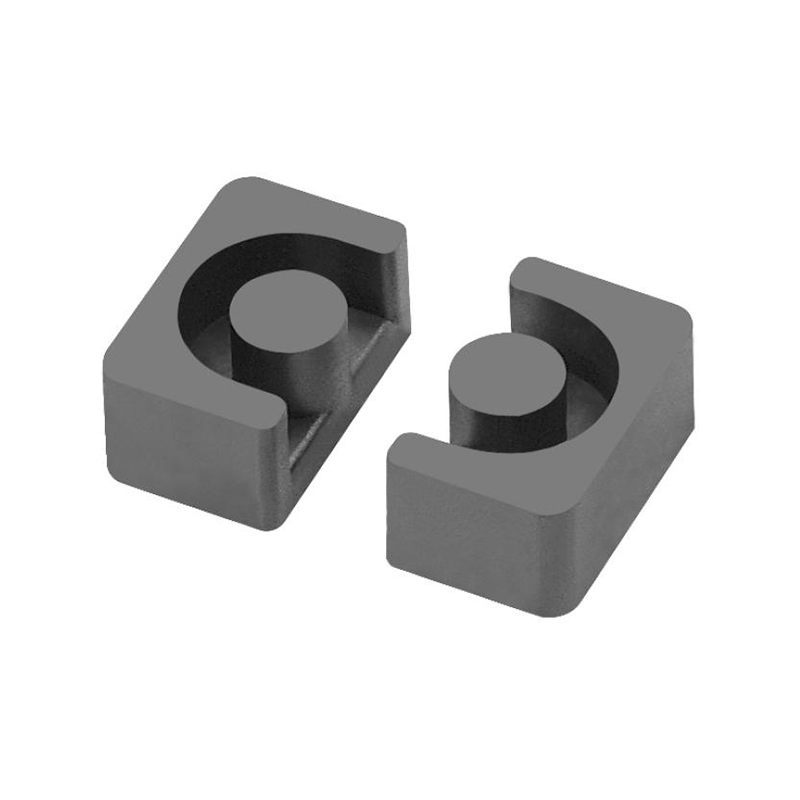

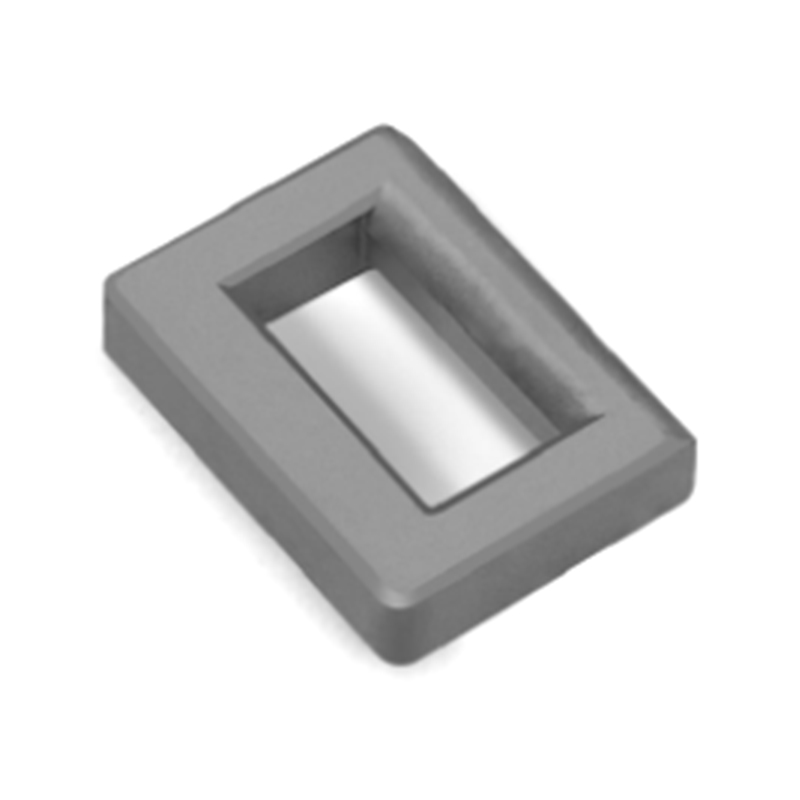

Common Core Shapes

MnZn ferrite cores are manufactured in diverse geometric configurations, each optimized for specific electromagnetic applications:

- Toroidal cores: Provide closed magnetic paths with minimal leakage flux, ideal for common-mode chokes and current transformers with typical outer diameters from 10 mm to 200 mm

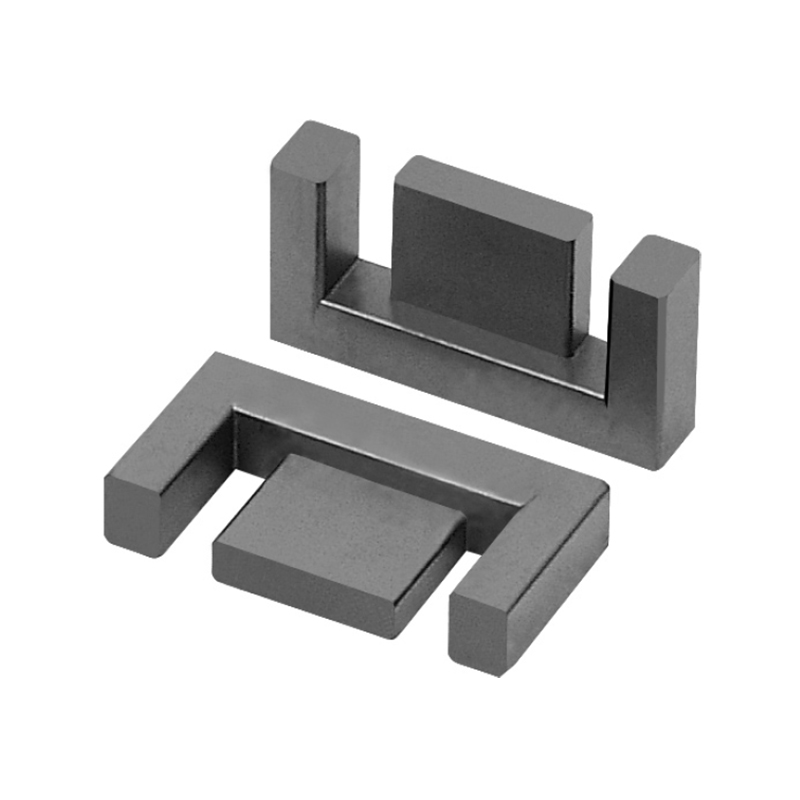

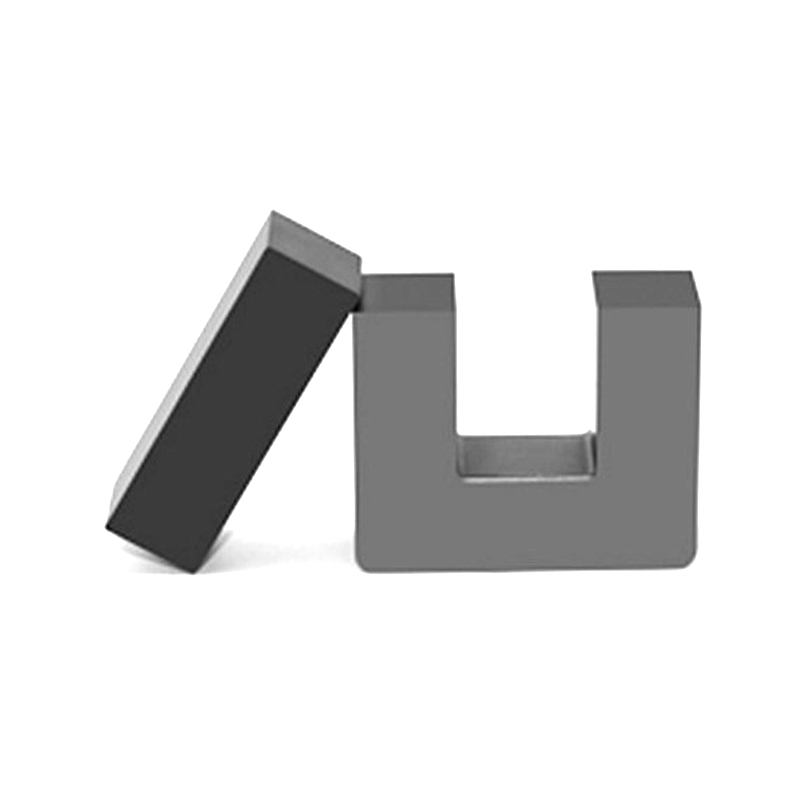

- E-cores and EE-cores: Enable easy winding assembly with bobbins, standard in power transformers and inductors with center leg gaps for energy storage

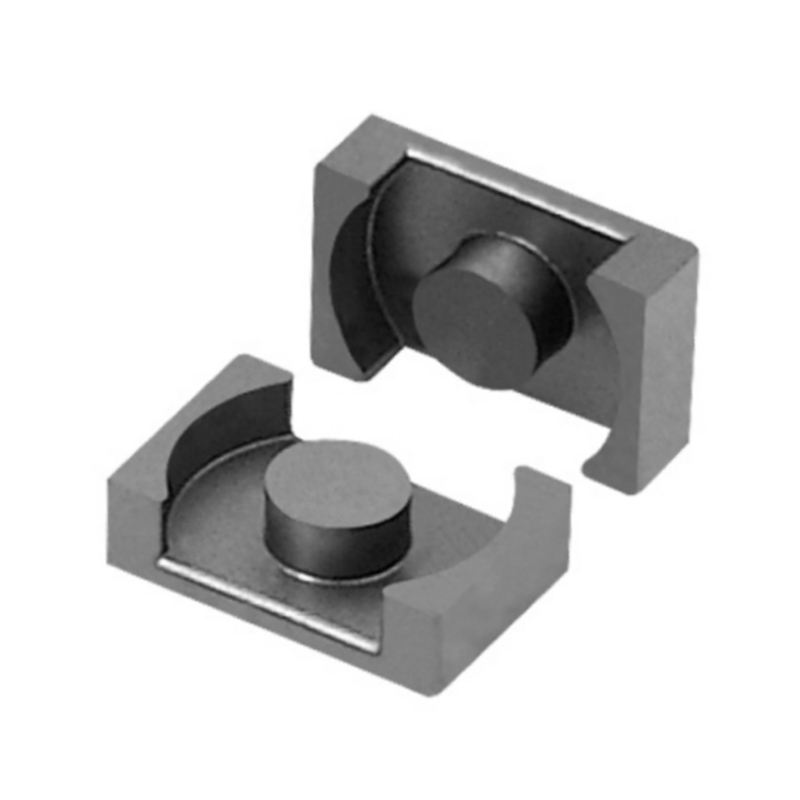

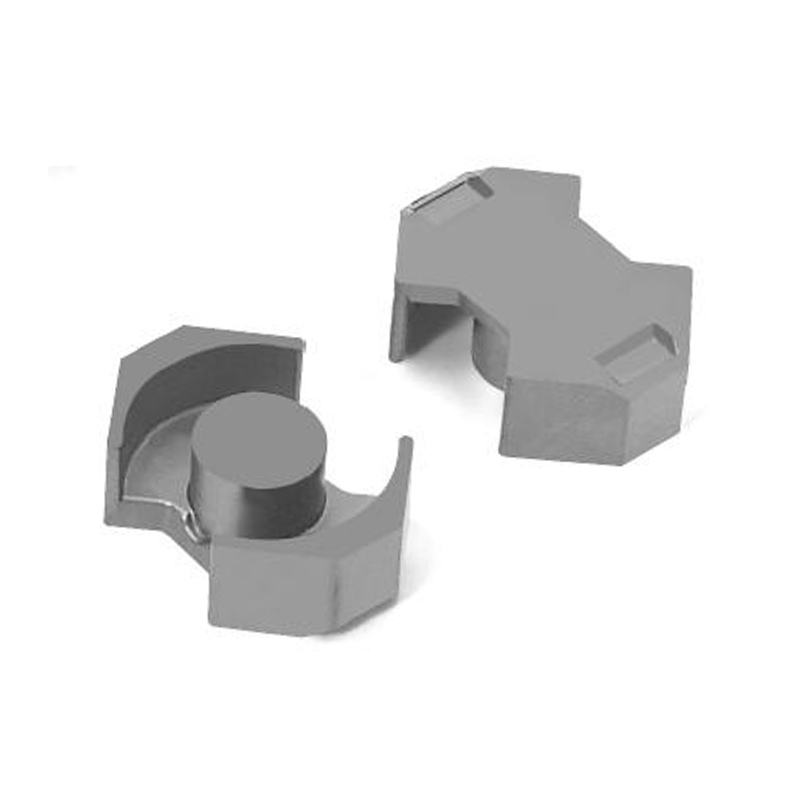

- Pot cores (RM, PM): Offer excellent magnetic shielding with approximately 95% of flux contained within the core structure

- EP and ETD cores: Combine low profile with high power handling capability, popular in planar transformers for space-constrained designs

- Beads and tubes: Suppress high-frequency noise on cables and leads with impedances ranging from 10 Ω to several kΩ at specified frequencies

Air Gap Implementation

Introducing air gaps into MnZn ferrite cores reduces effective permeability and increases saturation current capability—essential for power inductors handling DC bias. A 0.5 mm gap in an E42 core can reduce effective permeability from 2,300 to approximately 150, enabling energy storage applications with currents exceeding 10 A without core saturation. Gap placement affects fringing flux and winding losses, requiring careful electromagnetic modeling.

Primary Application Areas

Switch-Mode Power Supplies

MnZn ferrite cores serve as the magnetic foundation for SMPS transformers operating at 50-200 kHz in consumer electronics, industrial equipment, and telecommunications infrastructure. A typical ATX power supply utilizes an ETD44 or ETD49 core with power handling up to 500 W, leveraging low-loss ferrite grades to achieve conversion efficiencies exceeding 90%. The material's high saturation flux density permits compact designs with power densities reaching 15 W/cm³.

EMI Suppression Components

Common-mode chokes constructed with toroidal MnZn cores effectively attenuate electromagnetic interference in switching power supplies and motor drives. High-permeability grades (μi = 10,000-15,000) provide impedance values of 1-5 kΩ at 1 MHz with minimal DC resistance, suppressing conducted emissions without compromising signal integrity or power delivery efficiency. Ferrite beads address frequencies from 10 MHz to 1 GHz where NiZn compositions typically dominate.

Inductive Energy Storage

Gapped MnZn cores function in buck, boost, and flyback converter inductors storing magnetic energy during switching cycles. An E32 core with 0.3 mm total air gap achieves inductance values of 100-500 μH with saturation currents of 5-8 A, suitable for point-of-load regulators in computing and automotive electronics. The temperature rise under continuous operation must remain below 40°C to ensure reliability over 100,000-hour lifetimes.

Current Sensing and Measurement

Current transformers employing MnZn toroidal cores measure AC currents from milliamperes to kiloamperes with accuracy better than ±1% across frequency ranges of 50 Hz to 100 kHz. High-permeability materials minimize magnetizing current, enabling precise measurements at low primary currents. Split-core designs facilitate non-invasive installation in energy management systems and motor control applications.

Material Selection Criteria

Frequency-Dependent Selection

Selecting appropriate MnZn ferrite grades requires matching material characteristics to operating frequency:

- 10-50 kHz: High-permeability grades (μi > 8,000) maximize inductance while maintaining acceptable losses for line-frequency transformers and filter inductors

- 50-200 kHz: Power ferrites (μi = 2,000-3,500) balance permeability and core loss, optimized for mainstream SMPS applications with losses under 300 kW/m³

- 200-500 kHz: Low-loss grades minimize heating in high-frequency converters, critical for achieving 95%+ efficiency targets

- 500 kHz-1 MHz: Wide-band materials or transition to NiZn ferrites prevents excessive core losses that would negate switching frequency benefits

Power Handling and Thermal Management

Power dissipation in ferrite cores follows the relationship: P = V × f × B² × k, where V represents core volume, f is frequency, B is flux density, and k is the material loss coefficient. Designs targeting maximum power density operate at flux densities of 150-250 mT, requiring thermal analysis to ensure core temperatures remain below 100°C. Heat sinks, forced air cooling, or potting compounds enhance thermal conductivity from the typical 4-5 W/m·K of bare ferrite.

Environmental and Mechanical Factors

MnZn ferrites are brittle ceramic materials requiring careful handling during assembly. Tensile strength ranges from 50-100 MPa, making them vulnerable to mechanical stress and thermal shock. Coatings and encapsulation protect against humidity in harsh environments where moisture can degrade performance over time. Automotive and industrial applications specify extended temperature ranges (-40°C to +125°C) demanding specialized material formulations.

Manufacturing Process and Quality Factors

Production Methodology

MnZn ferrite cores undergo a multi-stage ceramic manufacturing process:

- Raw material preparation involves mixing iron oxide (Fe₂O₃), manganese compounds (MnO, Mn₃O₄), and zinc oxide (ZnO) with controlled stoichiometry

- Calcination at 800-1000°C forms the ferrite spinel structure

- Milling reduces particle size to 1-2 μm for optimal sintering behavior

- Pressing or extrusion shapes the green body with precise dimensional control

- Sintering at 1250-1350°C in controlled atmospheres achieves >95% theoretical density

- Grinding and assembly operations produce finished cores meeting ±1% dimensional tolerances

Quality Specifications

Critical quality parameters include permeability tolerance (typically ±25% for standard grades, ±10% for precision types), core loss verification at specified frequency and flux density, saturation flux density testing, and dimensional conformance. Manufacturers employ statistical process control to maintain batch-to-batch consistency, essential for high-volume production where component substitution must not affect circuit performance.

Comparison with Alternative Magnetic Materials

MnZn versus NiZn Ferrites

NiZn ferrites offer electrical resistivity 1000× higher than MnZn types (10⁵ vs 10² Ω·cm), enabling operation above 1 MHz where eddy currents would cripple MnZn performance. However, NiZn materials sacrifice low-frequency permeability (typical μi = 100-1,000) and saturation flux density (300-400 mT), making them unsuitable for power applications below 500 kHz. The crossover frequency where NiZn becomes preferable typically falls around 1-2 MHz depending on specific application requirements.

Ferrites versus Powder Cores

Iron powder, sendust, and MPP (molypermalloy powder) cores provide distributed air gaps that prevent saturation under high DC bias currents. These materials handle DC currents 3-5× higher than comparable ferrite cores without gapping. However, powder cores exhibit higher core losses at frequencies above 100 kHz and cost 2-4× more than MnZn ferrites. Applications requiring both AC performance and DC bias capability—such as PFC inductors—must carefully weigh these tradeoffs.

Ferrites versus Amorphous and Nanocrystalline Alloys

Amorphous metal ribbons achieve saturation flux densities of 1.4-1.6 Tesla—triple that of ferrites—with exceptionally low core losses at line frequencies. Nanocrystalline materials extend high performance to 100 kHz. These metal alloys excel in high-power transformers and specialty applications but cost 10-20× more than ferrite cores and require specialized winding techniques. MnZn ferrites remain dominant in cost-sensitive, medium-frequency applications where their combination of adequate performance and low cost proves unbeatable.

Design Guidelines and Practical Recommendations

Inductance Calculation

Inductance of wound ferrite cores follows: L = (μₑ × N² × Aₑ) / lₑ, where μₑ is effective permeability, N is turns count, Aₑ is effective core area, and lₑ is magnetic path length. Manufacturers provide AL values (inductance per turn squared) simplifying calculations: L = AL × N². For an E42 core with AL = 2500 nH/N², a 20-turn winding yields 1 mH inductance. Air gaps reduce AL proportionally to gap length, enabling precise inductance targeting.

Winding Techniques

Optimal winding practices minimize proximity and skin effect losses while ensuring adequate insulation. Litz wire reduces AC resistance at frequencies above 50 kHz where skin depth in copper falls below 0.3 mm. Layer winding with interleaving improves coupling in transformers, reducing leakage inductance to 1-2% of magnetizing inductance. Proper bobbin selection maintains creepage and clearance distances for safety certification compliance.

Testing and Validation

Critical validation measurements include:

- Inductance measurement at 10 kHz, 0.25 V using LCR meter to verify design calculations

- DC resistance confirming proper wire gauge and winding execution

- Saturation current testing under actual operating conditions revealing thermal and magnetic limits

- Temperature rise measurements at rated power identifying cooling requirements

- Frequency response characterization ensuring impedance behavior meets specifications

Future Trends and Developments

Ongoing research in MnZn ferrite materials focuses on extending frequency performance while reducing losses. Advanced dopants and sintering techniques have produced materials with core losses below 150 kW/m³ at 100 kHz, enabling switching frequencies to approach 500 kHz where silicon carbide and gallium nitride transistors operate most efficiently. Nanostructured ferrites show promise for achieving higher saturation flux densities exceeding 550 mT.

Wide-bandgap semiconductor adoption drives demand for ferrite cores operating at elevated temperatures. Material developments target stable operation to 150°C with minimal permeability variation, critical for automotive powertrains and renewable energy inverters where ambient temperatures routinely exceed 85°C. Integration of ferrite cores with planar magnetics and PCB embedding techniques reduces assembly costs while improving power density in next-generation converters.

Sustainability considerations influence material selection as manufacturers seek to reduce rare earth dependencies and improve recyclability. MnZn ferrites containing only abundant elements (Fe, Mn, Zn) position well for environmentally conscious designs. Process improvements cutting sintering temperatures by 50-100°C reduce embodied energy, aligning with global carbon reduction initiatives while maintaining the cost advantages that have made these materials ubiquitous in power electronics.

中文简体

中文简体