Soft Magnetic Ferrites: Properties, Applications & Selection Guide

What Are Soft Magnetic Ferrites

Soft magnetic ferrites are ceramic materials composed of iron oxide combined with other metal oxides (such as manganese, zinc, nickel, or magnesium) that exhibit high magnetic permeability and low coercivity. Unlike hard ferrites used in permanent magnets, soft ferrites are designed to be easily magnetized and demagnetized, making them ideal for high-frequency applications where rapid magnetic field changes occur. They typically operate effectively at frequencies ranging from 1 kHz to over 1 GHz, with electrical resistivity values between 10² to 10⁹ Ω·cm—approximately one million times higher than metallic magnetic materials.

The two primary categories are manganese-zinc (MnZn) ferrites and nickel-zinc (NiZn) ferrites. MnZn ferrites dominate lower frequency applications (typically below 5 MHz) with initial permeability values ranging from 750 to 15,000, while NiZn ferrites excel at higher frequencies (1 MHz to 1 GHz) with permeability values between 10 and 1,500. This fundamental distinction determines their respective applications in modern electronics.

Chemical Composition and Crystal Structure

Soft magnetic ferrites possess a spinel crystal structure with the general chemical formula MFe₂O₄, where M represents divalent metal ions. This inverse spinel structure features oxygen ions arranged in a face-centered cubic lattice with metal ions occupying tetrahedral (A) and octahedral (B) interstitial sites. The magnetic properties arise from the antiparallel alignment of magnetic moments between A and B sites, resulting in a net magnetic moment.

Common Ferrite Compositions

| Ferrite Type | Typical Composition | Curie Temperature | Resistivity (Ω·cm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MnZn | Mn₀.₆Zn₀.₄Fe₂O₄ | 200-300°C | 1-10 |

| NiZn | Ni₀.₃Zn₀.₇Fe₂O₄ | 300-500°C | 10⁶-10⁹ |

| MgZn | Mg₀.₅Zn₀.₅Fe₂O₄ | 250-350°C | 10⁵-10⁷ |

Manufacturing involves mixing metal oxide powders, calcining at 900-1000°C, milling to fine particle size (typically 1-2 μm), pressing or molding into desired shapes, and sintering at temperatures between 1100-1400°C in controlled atmospheres. The sintering atmosphere critically affects the Fe²⁺/Fe³⁺ ratio, which directly influences electrical resistivity and magnetic losses.

Key Magnetic Properties and Performance Characteristics

The performance of soft magnetic ferrites is defined by several critical parameters that determine their suitability for specific applications. Understanding these properties enables engineers to select optimal materials for transformer cores, inductors, and electromagnetic interference suppression components.

Initial Permeability and Frequency Response

Initial permeability (μᵢ) represents the material's ability to conduct magnetic flux at low field strengths. High-permeability MnZn ferrites can achieve μᵢ values exceeding 10,000 at room temperature, while NiZn ferrites typically range from 20 to 1,500. The permeability decreases with increasing frequency due to domain wall motion damping and spin rotation lag effects. For MnZn ferrites, permeability remains relatively stable up to approximately 1-2 MHz, while NiZn materials maintain performance beyond 100 MHz.

Core Loss Mechanisms

Total core losses comprise three components:

- Hysteresis loss: Energy dissipated during magnetization cycling, proportional to frequency and flux density

- Eddy current loss: Resistive heating from induced currents, increasing with the square of frequency

- Residual loss: Additional losses at high frequencies from domain wall resonance and spin damping

Modern power ferrites achieve core losses as low as 200-300 kW/m³ at 100 kHz and 200 mT, enabling efficient switched-mode power supply designs. The high electrical resistivity of ferrites minimizes eddy current losses, providing a significant advantage over metallic magnetic materials at frequencies above 20 kHz.

Temperature Stability

Permeability exhibits strong temperature dependence, particularly near the Curie temperature where magnetic ordering disappears. Commercial ferrites are formulated with specific temperature coefficients to match application requirements. Some materials achieve ±20% permeability variation from -40°C to +125°C, while specialized grades offer ±5% stability over narrower ranges for precision filter applications.

Industrial Applications Across Electronics Sectors

Soft magnetic ferrites serve as essential components in power conversion, signal processing, and electromagnetic compatibility solutions across diverse industries. Their unique combination of high permeability, low losses, and electrical insulation enables compact, efficient designs impossible with metallic cores.

Power Electronics and Energy Conversion

Switched-mode power supplies (SMPS) represent the largest application segment, with ferrite transformers and inductors operating at frequencies between 50 kHz and 1 MHz. A typical laptop charger contains 3-5 ferrite components handling power densities exceeding 50 W/cm³. High-saturation MnZn ferrites (saturation flux density >500 mT) enable miniaturization while maintaining efficiency above 95%.

Photovoltaic inverters utilize specialized ferrite cores in DC-DC converters and output filters, processing kilowatts of power with core losses below 500 mW/cm³. The automotive industry has rapidly adopted ferrites for electric vehicle onboard chargers (operating at 100-200 kHz) and DC-DC converters managing 400-800V battery systems.

Telecommunications and Data Infrastructure

Common-mode chokes using NiZn ferrite toroids provide electromagnetic interference suppression in high-speed data cables (USB, HDMI, Ethernet). These components attenuate noise between 1 MHz and 1 GHz by 20-40 dB without affecting differential signal integrity. The global deployment of 5G infrastructure has increased demand for wide-bandwidth ferrite materials with stable impedance characteristics across temperature and frequency.

Wireless charging systems for smartphones and electric vehicles employ ferrite sheets (100-300 μm thick) to concentrate magnetic flux and shield nearby electronics. These flexible ferrite films achieve permeability values of 100-300 at operating frequencies around 100-200 kHz, improving power transfer efficiency by 15-25% compared to unshielded coils.

Industrial Automation and Sensing

Inductive proximity sensors incorporate ferrite cores to enhance detection range and sensitivity. Ferrite pot cores in these sensors enable detection distances up to 60 mm for standard M18 form factors. Pulse transformers using high-frequency NiZn ferrites transmit gate drive signals in motor controllers and industrial inverters, providing galvanic isolation while preserving nanosecond-scale pulse edges.

Material Selection Criteria for Design Engineers

Selecting the appropriate soft ferrite material requires balancing multiple performance factors against cost, availability, and manufacturing constraints. A systematic approach considers operating frequency, flux density, temperature range, and loss budget to identify optimal candidates.

Frequency Domain Considerations

The primary selection criterion divides materials by frequency range:

- Below 100 kHz: High-permeability MnZn ferrites (μᵢ = 5,000-15,000) for line-frequency transformers and filter inductors

- 100 kHz to 2 MHz: Power MnZn ferrites (μᵢ = 2,000-3,000) optimized for low losses in SMPS applications

- 2 MHz to 100 MHz: Low-loss NiZn ferrites (μᵢ = 100-800) for RF chokes and wideband transformers

- Above 100 MHz: High-resistivity NiZn ferrites (μᵢ = 10-100) for EMI suppression and antenna applications

Power Handling and Thermal Management

Saturation flux density limits the maximum energy storage capacity. Standard power ferrites saturate at approximately 400-500 mT at 25°C, decreasing to 300-350 mT at 100°C. Designs typically operate at 60-80% of saturation to maintain linearity and avoid abrupt inductance collapse. Core geometry selection balances magnetic path length, winding window area, and surface area for heat dissipation.

Temperature rise calculations must account for both core losses and copper losses. A well-designed inductor maintains core temperature below the material's rated limit (typically 100-140°C for commercial grades) with appropriate heat sinking or forced air cooling. Thermal conductivity of ferrites ranges from 3-5 W/m·K, requiring careful attention to hot spot formation in high-power applications.

Cost-Performance Trade-offs

Material costs vary significantly based on composition and processing complexity. Standard MnZn power ferrites represent the most economical choice for volume production, with raw material costs around $5-15 per kilogram. High-performance low-loss grades command 2-3× premiums, justified in applications where efficiency directly impacts system value (data centers, renewable energy). NiZn ferrites cost 30-50% more than comparable MnZn materials due to higher raw material costs and processing complexity.

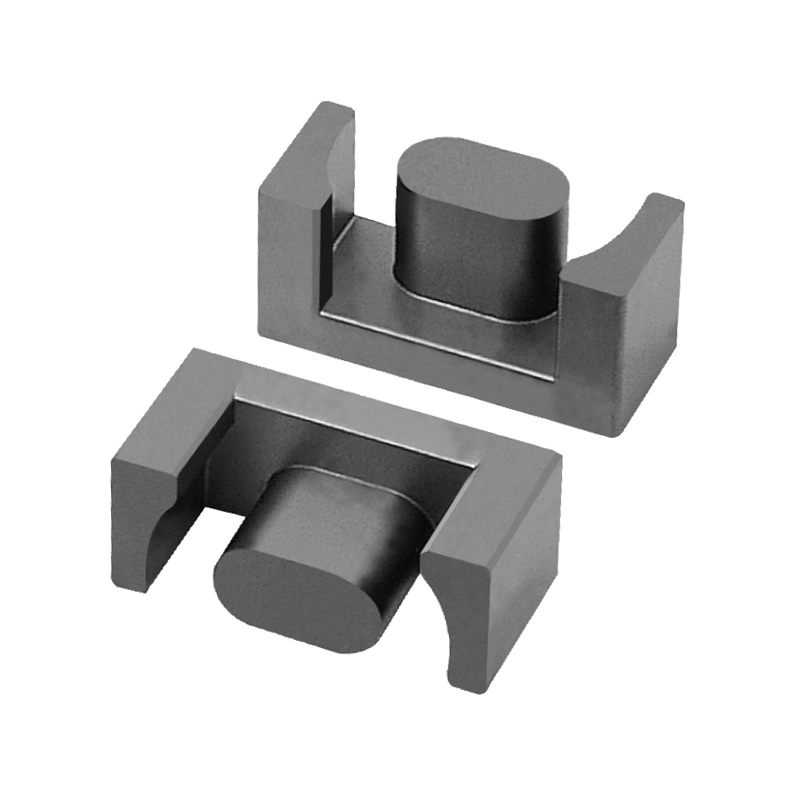

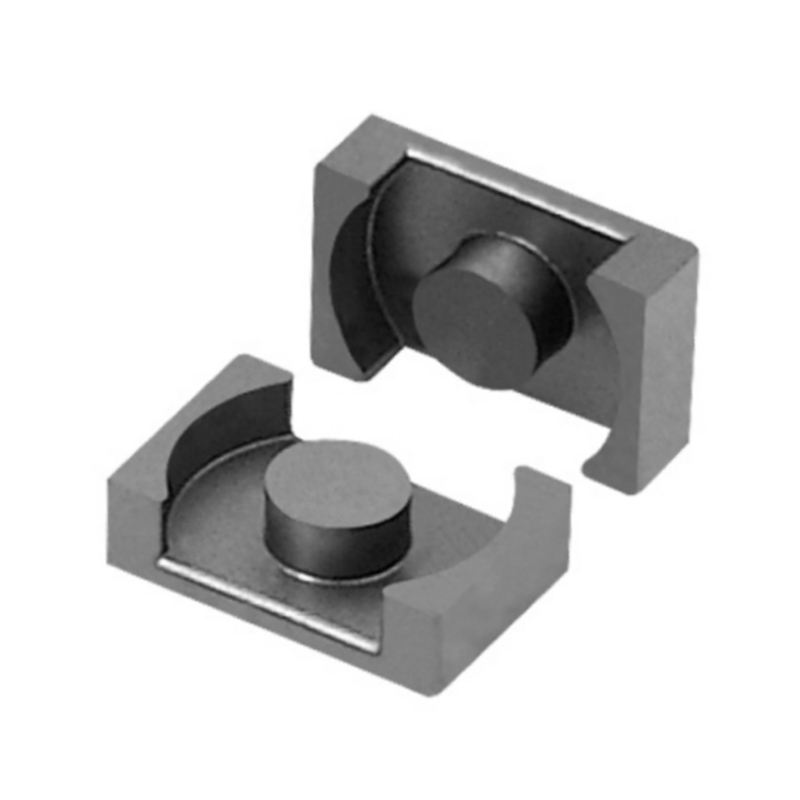

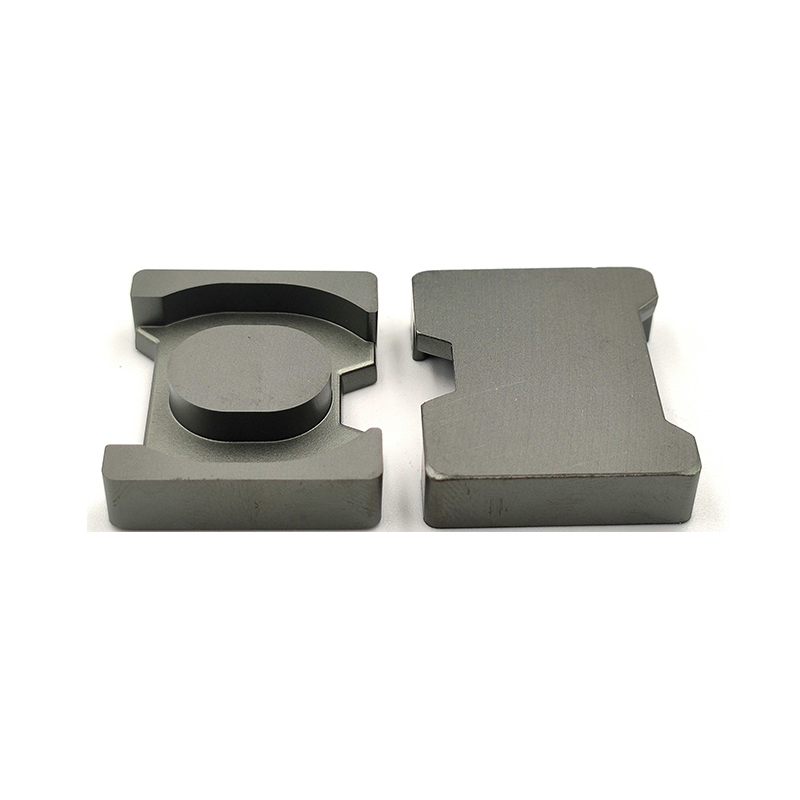

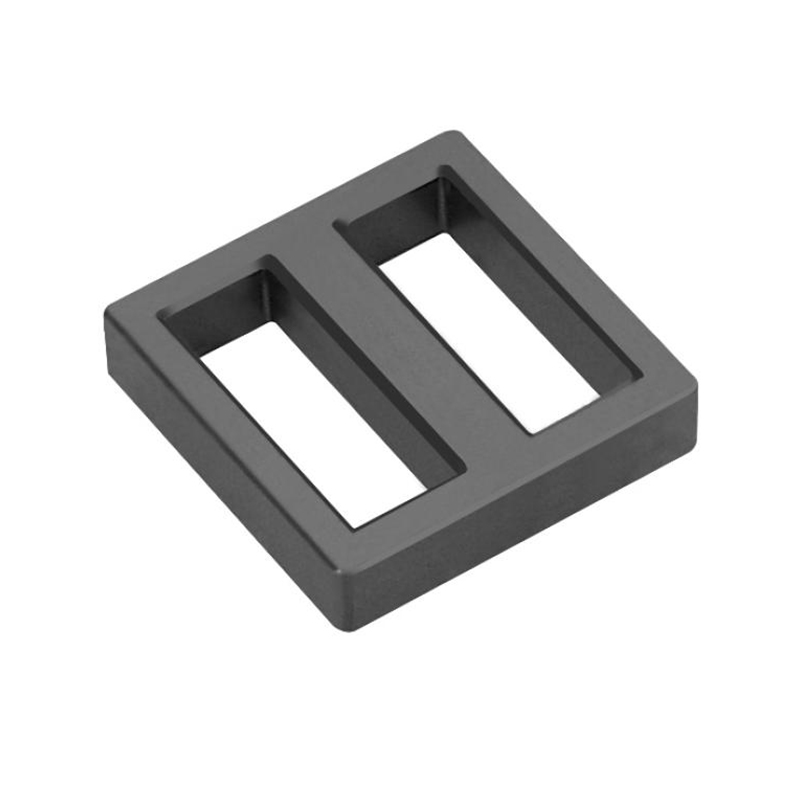

Core Geometries and Form Factors

Ferrite cores are manufactured in standardized shapes optimized for specific applications and winding requirements. The geometry selection affects magnetic path length, effective area, winding ease, and electromagnetic shielding characteristics.

Common Core Configurations

| Core Type | Typical Applications | Key Advantages | Size Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Toroid | EMI filters, current sensors | Low leakage, self-shielding | 5-100mm OD |

| E-core | Transformers, inductors | Easy bobbin winding, modular | E10-E65 |

| Pot core | Precision inductors, filters | Excellent shielding, adjustable | P7-P66 |

| RM core | SMPS, high-power converters | Round center post, good cooling | RM4-RM14 |

| Planar core | Low-profile PCB transformers | Ultra-low profile, repeatable | 3-25mm height |

Air gap introduction modifies inductance and prevents saturation in DC-biased applications. Distributed gap materials mix ferrite powder with non-magnetic spacers, providing effective permeability values from 15 to 200 with excellent temperature stability and reduced gap fringing losses compared to discrete gaps.

Recent Developments and Future Trends

The soft ferrite industry continues advancing material formulations and processing methods to meet evolving requirements in power electronics, wireless systems, and automotive applications. Current research focuses on improving performance at temperature extremes, increasing saturation flux density, and developing environmentally sustainable manufacturing processes.

High-Temperature Materials for Automotive Applications

Electric vehicle powertrains demand ferrite components operating reliably at junction temperatures exceeding 150-180°C. Modified MnZn compositions incorporating rare earth dopants achieve stable performance up to 200°C, enabling direct integration with power semiconductors and eliminating intermediate cooling stages. These materials maintain core losses below 600 kW/m³ at 100 kHz and 200 mT even at elevated temperatures.

Nanocrystalline and Hybrid Materials

Composite materials combining soft ferrites with metallic magnetic nanoparticles achieve saturation flux densities approaching 1.0-1.2 T while retaining the high resistivity benefits of ceramic ferrites. These hybrid cores enable transformer designs with 30-40% volume reduction compared to conventional ferrites at equivalent power ratings. Commercial introduction targets renewable energy inverters and data center power supplies where size and efficiency directly impact total cost of ownership.

Wide Bandgap Semiconductor Integration

Silicon carbide (SiC) and gallium nitride (GaN) power devices operate at switching frequencies from 500 kHz to several MHz, pushing ferrite requirements toward lower losses and higher frequency stability. New NiZn ferrite grades optimized for 1-10 MHz range exhibit core losses below 1,000 kW/m³ at 1 MHz and 50 mT, supporting the transition to multi-MHz power conversion topologies with efficiency exceeding 99%.

Environmental and Sustainability Initiatives

Industry efforts to reduce environmental impact include development of lead-free and heavy-metal-free formulations, implementation of closed-loop water recycling in manufacturing, and energy recovery from high-temperature sintering processes. Life cycle assessments indicate that ferrite component production generates 60-70% lower CO₂ emissions compared to equivalent metallic core manufacturing, supporting broader electronics industry decarbonization goals.

Testing and Quality Assurance Methods

Rigorous testing protocols ensure soft ferrite components meet specified electrical, magnetic, and mechanical performance requirements. Manufacturers employ standardized measurement techniques defined by IEC and ASTM standards to characterize materials and validate production quality.

Magnetic Property Measurements

Initial permeability testing uses impedance analyzers with toroidal samples wound with precise turn counts. Measurements at 10 kHz and 25°C provide baseline values, while temperature sweeps from -40°C to 150°C characterize thermal stability. B-H loop tracers quantify saturation flux density, coercivity, and hysteresis losses under controlled excitation conditions. Modern systems achieve measurement accuracy within ±2% for permeability and ±5% for core losses.

Reliability and Longevity Testing

Accelerated life testing subjects samples to elevated temperature (125-150°C) and humidity (85% RH) for 1,000-2,000 hours to verify long-term stability. Thermal shock cycling between temperature extremes identifies susceptibility to cracking or delamination. High-voltage dielectric strength testing confirms insulation integrity exceeds application requirements, typically demonstrating breakdown voltages above 1,500 V/mm for ferrite ceramics.

Design Calculations and Practical Examples

Successful ferrite component design requires accurate calculation of core geometry, winding turns, and operating flux density. The following example demonstrates the design process for a common power inductor application.

Power Inductor Design Example

Consider a 100 μH inductor for a 3.3V to 12V boost converter operating at 200 kHz with 5A maximum current:

- Energy storage requirement: E = ½LI² = ½(100×10⁻⁶)(5²) = 1.25 mJ

- Select MnZn power ferrite (μᵢ = 2,500, Bsat = 480 mT at 100°C)

- Operating flux density: Target 300 mT (62% of saturation) for temperature margin

- Required core volume: Vc ≥ 2E/(Bmax²/μ₀) ≈ 2.1 cm³

- Select ETD29 core (Ae = 76 mm², le = 68 mm, Ve = 5,170 mm³)

The calculation yields approximately 52 turns of wire to achieve 100 μH with an air gap of 0.5 mm. Core loss at 200 kHz and 300 mT peak flux density is approximately 450 kW/m³, resulting in 2.3W dissipation in the selected core—acceptable for forced air cooling.

中文简体

中文简体