What is the difference between gapped and ungapped MnZn ferrite cores?

The Fundamental Role of the Air Gap

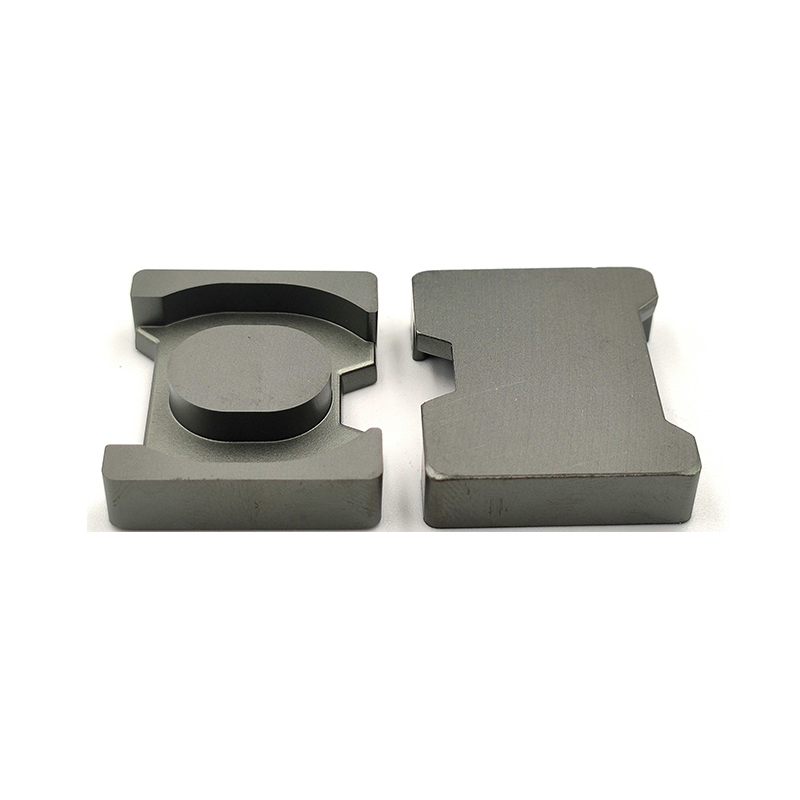

At its core, the difference between gapped and ungapped MnZn ferrite core lies in the deliberate introduction of a physical discontinuity in the magnetic path. An ungapped core is a single, homogeneous piece of ferrite. A gapped core has a thin, precise air gap (or multiple distributed gaps) inserted, often by grinding the center leg of an E-core or using spacers between core halves. This air gap, though tiny, fundamentally alters the magnetic circuit's behavior by increasing its reluctance. It acts as a barrier that magnetic flux lines must cross, storing energy in the gap's magnetic field and providing a critical buffer against saturation under high current or DC bias conditions. This simple mechanical modification is the primary tool designers use to tailor the core's effective magnetic properties for specific circuit functions.

Contrasting Magnetic Properties and Performance

The presence or absence of an air gap leads to distinct performance profiles, making each type suitable for different applications.

Key Property Changes Introduced by Gapping

Gapping drastically lowers the effective permeability (µe) of the core compared to its initial material permeability (µi). For example, a high-permeability (µi ~ 3000) material can be reduced to a µe of 100 or less with an appropriate gap. This reduction brings several critical changes:

- DC Bias Handling: The gapped core can sustain a much higher DC current or superimposed AC flux before reaching saturation. The gap "linearizes" the B-H curve, making inductance more stable over a wide current range.

- Energy Storage: The air gap becomes the primary site for magnetic energy storage (W = ½ L I²). This is essential for inductors in switching power supplies that must handle large ripple currents.

- Thermal Stability: The temperature dependence of permeability is significantly reduced in a gapped structure, leading to more predictable performance across operating temperatures.

- Core Loss Trade-off: While the gap itself does not generate loss, the lower µe often forces the use of more turns to achieve the same inductance. This can increase copper loss. Furthermore, for the same peak flux density, a gapped core may experience a slightly wider flux swing, potentially impacting AC core loss, though it prevents saturation-induced catastrophic loss.

Application-Specific Selection: Where Each Core Excels

The choice is never about which is universally better, but about which is correct for the circuit's function.

Ungapped MnZn Ferrite Core Applications

Ungapped cores are used where high permeability and maximum coupling efficiency are paramount.

- Signal and Wideband Transformers: In telecommunications and analog circuits, they provide high inductance with minimal turns, enabling excellent coupling over a broad frequency range.

- Common Mode Chokes: The high µi provides a large impedance to common-mode noise without saturating from the differential signal currents, which cancel out in the core.

- Current Transformers (Sensing): They operate with near-zero net DC bias, leveraging high permeability for accurate signal reproduction at low excitation levels.

Gapped MnZn Ferrite Core Applications

Gapped cores are essential for components that must handle unidirectional magnetic polarization.

- Power Inductors & PFC Chokes: In boost, buck, and flyback converters, the gap allows the inductor to store energy from the switching cycle without saturating under high DC load currents.

- Flyback Transformer: This component is, in function, a gapped coupled inductor. The gap sets the primary inductance value, controlling the energy storage per cycle and preventing core saturation due to the primary DC current.

- Filter Inductors in SMPS Output Stages: They smooth the rectified output, requiring stable inductance under significant DC bias.

Practical Design and Implementation Considerations

Working with these cores requires attention to specific physical and electrical details.

Designing with a Gapped Core

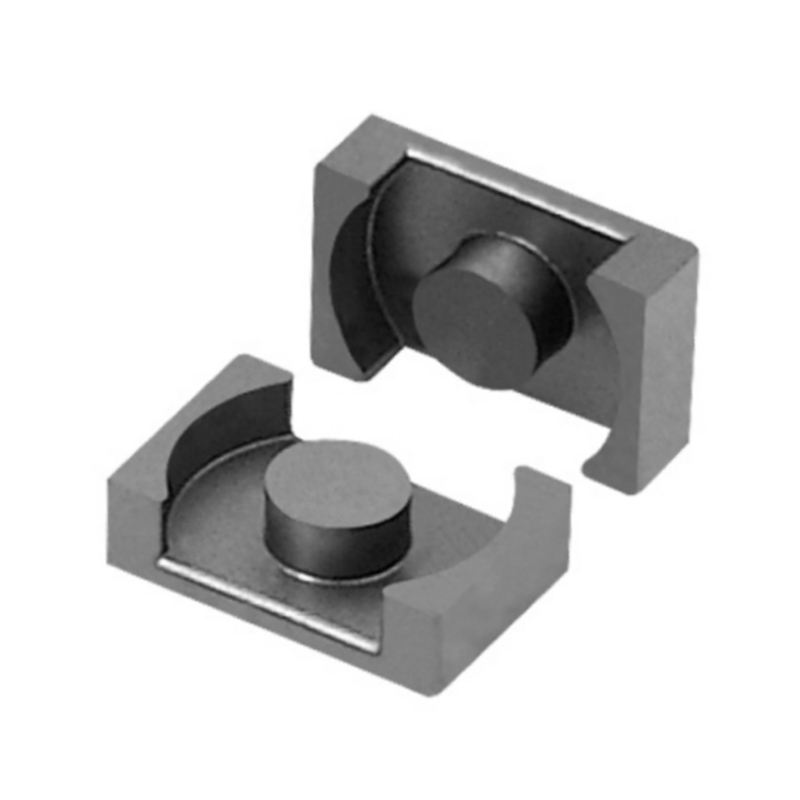

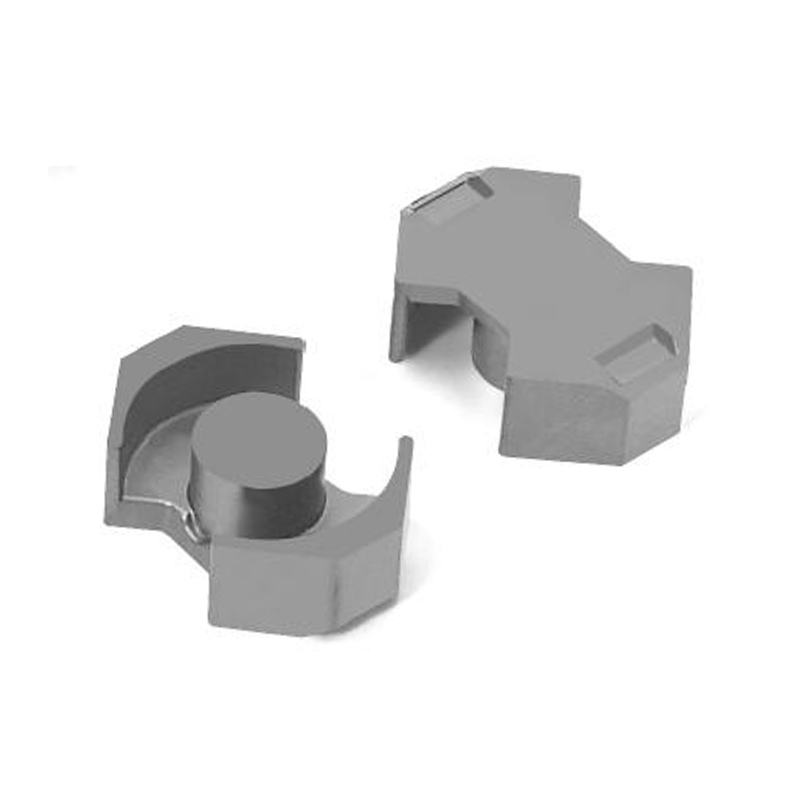

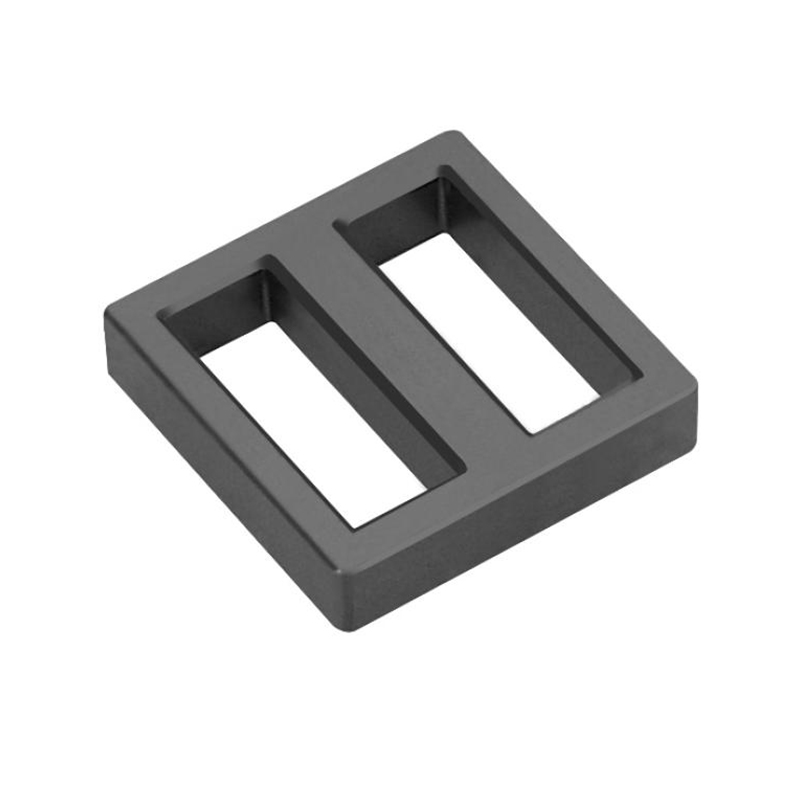

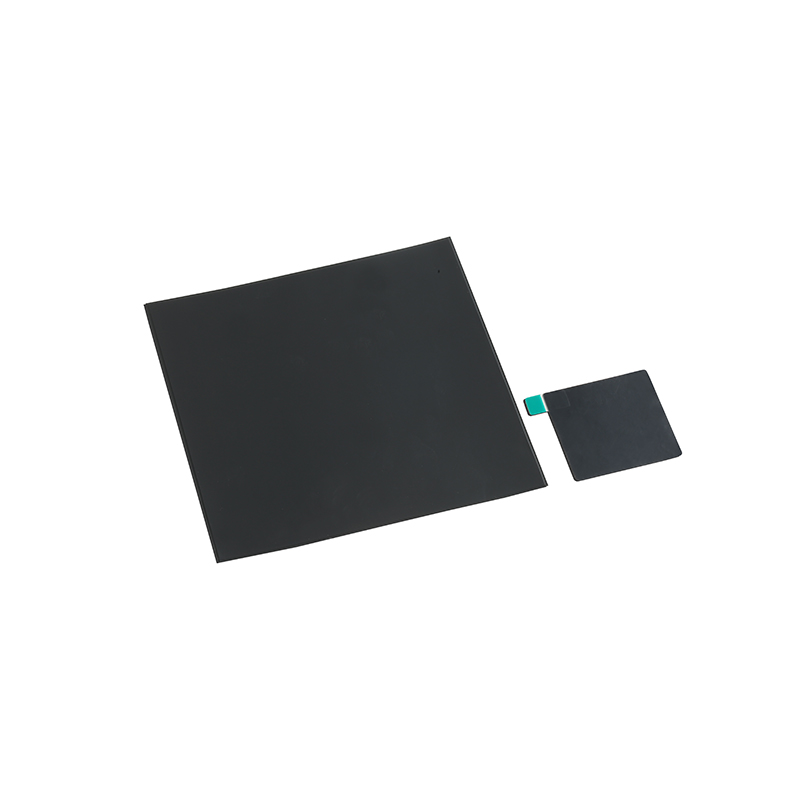

When using a gapped core, the effective parameters become the design focus. You must calculate the required gap length based on target inductance (AL value), saturation current, and DC bias. Fringing flux around the gap can cause localized heating and increase effective core loss, so core shapes with distributed gaps (like PQ or RM cores) are often preferred for high-power applications. Securing the core halves consistently is critical, as the gap length must be maintained; vibration or uneven pressure can alter inductance.

Designing with an Ungapped Core

Here, the intrinsic material properties dominate. Care must be taken to avoid any DC component that could drive the core into saturation, as it has little inherent tolerance. Winding techniques to improve coupling and minimize leakage inductance are key. Thermal management is also crucial, as ungapped cores in high-frequency transformers can experience significant core loss density.

Comparative Summary Table

| Feature | Ungapped MnZn Core | Gapped MnZn Core |

| Primary Function | Signal transformation, coupling, noise suppression | Energy storage, handling DC bias |

| Key Advantage | Very high permeability, maximum coupling efficiency | High saturation flux density, stable inductance under DC bias |

| DC Bias Tolerance | Very Low | High |

| Effective Permeability (µe) | Close to material µi (e.g., 1500-10000) | Drastically reduced by gap (e.g., 50-500) |

| Typical AL Value | High (nH/turn²) | Low to moderate (nH/turn²) |

| Dominant Loss Concern | AC core loss (hysteresis & eddy current) | Copper loss (due to more turns) & fringing flux effects |

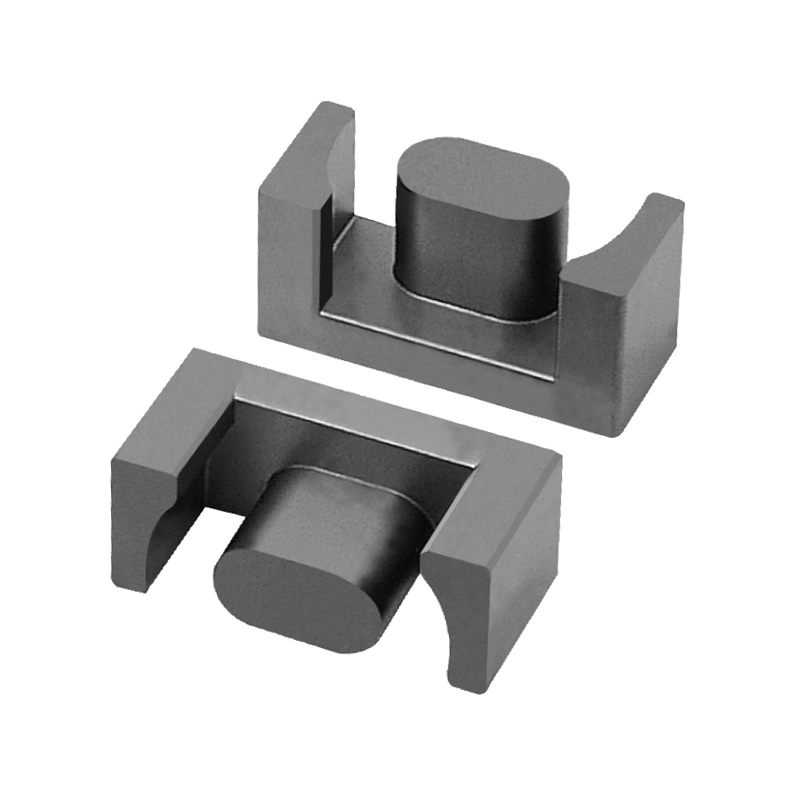

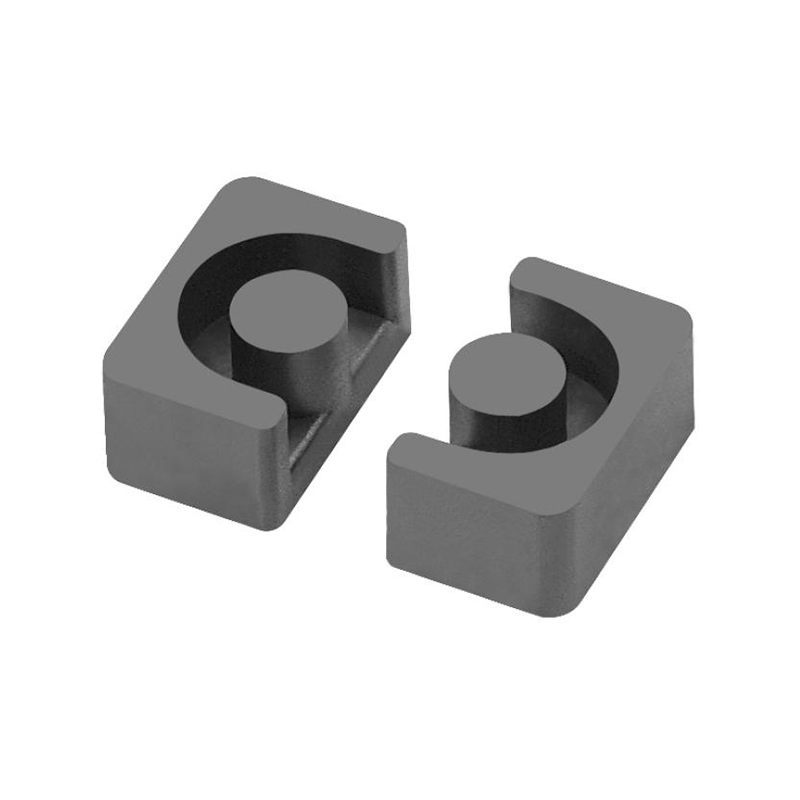

| Typical Core Shapes | Toroids, E-cores, RM cores for transformers | E-cores, ETD, PQ, Pot cores (often pre-gapped) |

Conclusion: Making the Informed Choice

Selecting between a gapped and ungapped MnZn ferrite core is a fundamental decision in magnetic design. It hinges on a single question: Does my component need to store substantial energy from a DC or heavily biased magnetic field? If the answer is yes, as in power inductors and flyback transformers, a gapped core is non-negotiable. Its engineered discontinuity provides the robust, linearized performance required. If the answer is no, and the goal is efficient signal transfer or noise filtering with minimal excitation, the high permeability and simplicity of an ungapped core make it the optimal and more efficient choice. Understanding this core distinction ensures the magnetic component works not just as a passive part, but as a reliably optimized element within the larger electronic system.

中文简体

中文简体