Optimizing MnZn Ferrite Core Performance in Power Electronics

This article provides a practical, in-depth exploration of MnZn ferrite core, including material characteristics, loss mechanisms, selection criteria for power electronics, and effective design strategies for engineers seeking optimized magnetic performance.

Understanding MnZn Ferrite Core Fundamentals

MnZn (Manganese‐Zinc) ferrite cores are a class of soft magnetic materials widely used in power conversion, EMI suppression, and transformer applications. Their high permeability, relatively low cost, and stable performance at frequencies from a few kHz up to several MHz make them ideal for switching power supplies and inductors. Unlike hard magnetic materials used in permanent magnets, MnZn ferrites are engineered for low hysteresis and eddy current losses.

At the material level, MnZn ferrite is a polycrystalline ceramic composed primarily of MnO, ZnO, and Fe₂O₃, sintered to achieve controlled grain size and density. The resulting microstructure and composition directly influence key properties such as initial permeability (µᵢ), saturation flux density (Bₛ), Curie temperature (T?), and core loss characteristics.

Critical Material Properties and Their Impact

Permeability and Frequency Response

Permeability defines a core’s ability to concentrate magnetic flux. MnZn ferrites typically feature high initial and maximum relative permeability (µᵣ), often ranging between 1000 and 15,000 depending on grade. High permeability reduces magnetizing current and aids in achieving inductance targets with fewer turns. However, permeability decreases with frequency, and high‐µ grades may exhibit reduced performance near the upper end of the ferrite’s usable frequency range.

Core Loss Mechanisms

Core loss in MnZn ferrites originates from three primary mechanisms:

- Hysteresis loss, proportional to frequency and flux swing, linked to domain wall motion.

- Eddy current loss, minimized by high electrical resistivity.

- Residual loss, including microstructural imperfections and domain pinning effects.

Minimizing core loss requires balancing permeability, resistivity, and grain structure. For example, grades optimized for low loss at 100 kHz will differ in composition from those designed for low‐frequency applications.

Saturation Flux Density and Temperature Performance

Saturation flux density (Bₛ) indicates the core’s ability to carry magnetic flux before nonlinear effects degrade inductance. Typical MnZn ferrites have Bₛ around 0.4–0.5 T. Operating near saturation increases losses and distortion. Temperature also affects performance: ferrite materials commonly have a negative temperature coefficient of permeability and must be chosen with a Curie point well above operating temperature to prevent performance drift.

Selecting MnZn Ferrite Cores for Power Applications

Selecting the right core requires matching material properties with application requirements. Key criteria include operating frequency, power level, thermal limits, mechanical constraints, and cost.

Application Categories and Core Preferences

| Application | Typical Frequency Range | Preferred MnZn Grade | Notes |

| Switch‐mode power supply transformers | 20 kHz – 200 kHz | Medium‑µ, low‑loss | Balanced permeability & loss |

| Flyback inductors | 50 kHz – 500 kHz | Low‑loss at high frequency | Prioritize low loss over max µ |

| EMI suppression choke | 100 kHz – 1 MHz | High‑µ, wide‑band | Broad frequency range |

Consider multi‐criteria decision tradeoffs: high µ improves inductance but often at the cost of increased core loss at higher frequencies. Evaluate vendor datasheets under application‐specific flux density and temperature conditions.

Designing with MnZn Ferrite Cores: Practical Steps

Once the core grade is selected, design tasks include calculating inductance, estimating core losses, and managing thermal limits. The following processes ensure a robust design.

Calculating Inductance and Turns

The basic inductance equation for a core with N turns is:

- L = (µᵣµ₀A / l) × N²

where µᵣ is relative permeability, µ₀ is the vacuum permeability, A is effective core cross‐sectional area, and l is magnetic path length. Choose N to achieve the target inductance while staying within practical winding volume and DC resistance constraints.

Be aware of the effect of air gaps: for inductors, adding an air gap reduces effective permeability but increases energy storage capability. Calculate the effective inductance by considering the gap’s reluctance in series with the ferrite’s reluctance.

Estimating Core Loss

Use vendor‐provided core loss tables or graphs which express loss as watts per unit volume at specific flux densities and frequencies. Loss increases nonlinearly with both frequency and flux density. A common practical approach:

- Select a flux density target well below Bₛ to limit loss.

- Adjust turns to reduce flux at high current levels.

- Verify with finite element or lookup tools when available.

Accurate loss estimates are essential for thermal design.

Thermal Management Strategies

Core losses convert to heat that must be dissipated. Strategies include:

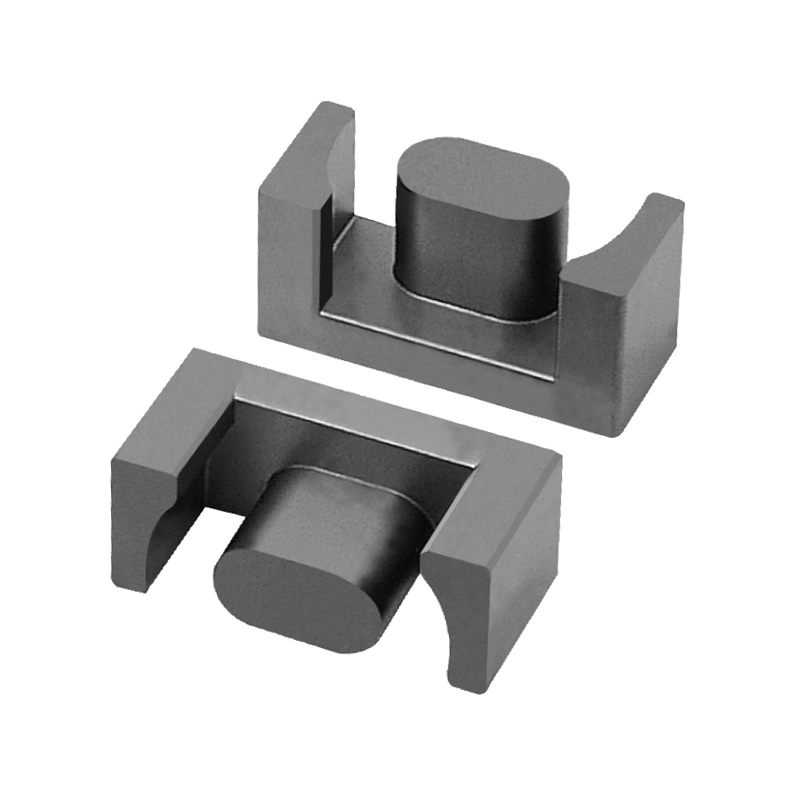

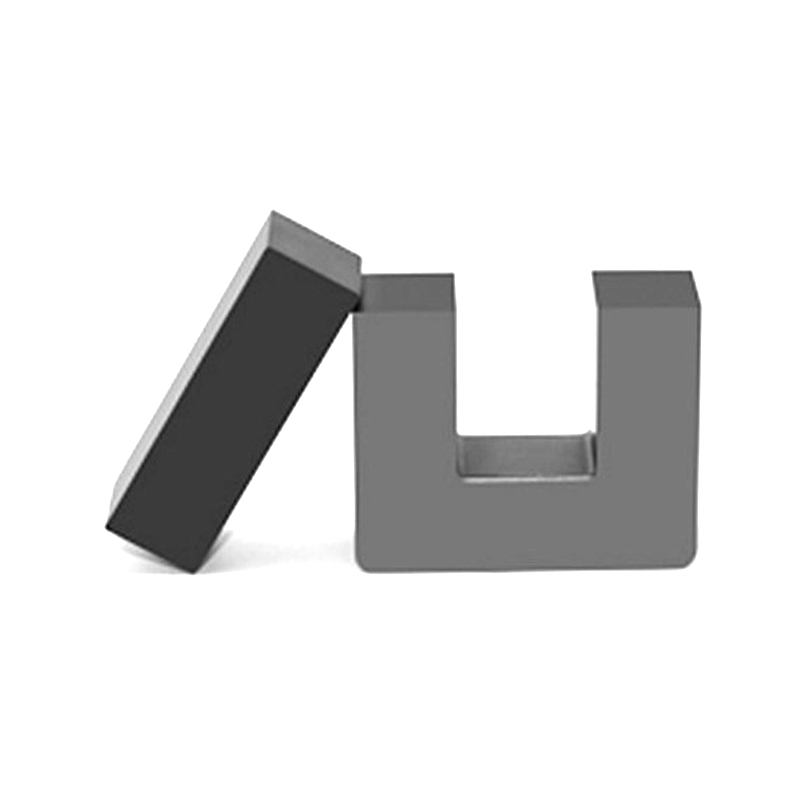

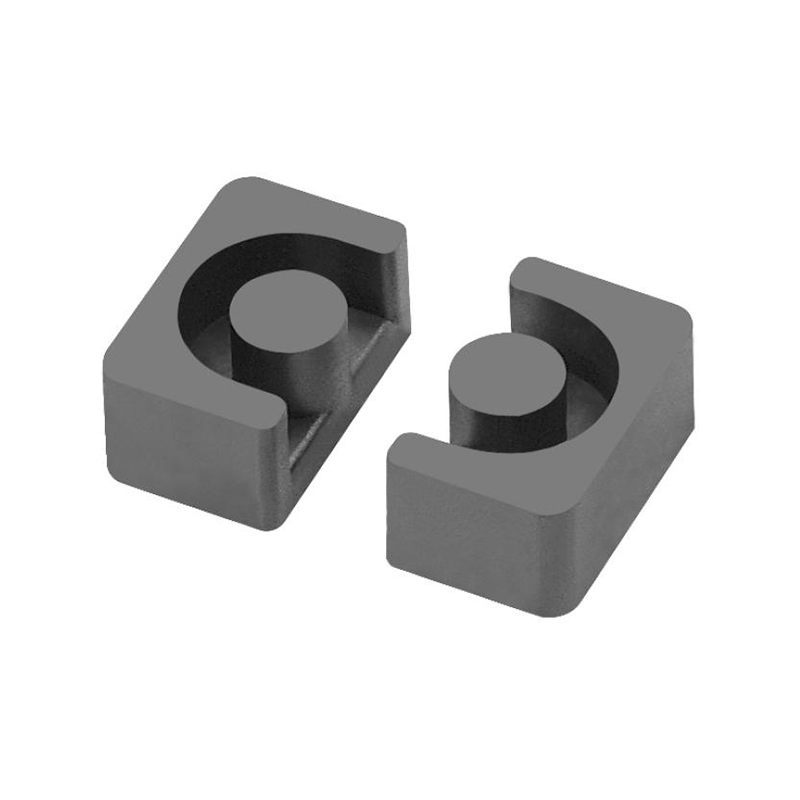

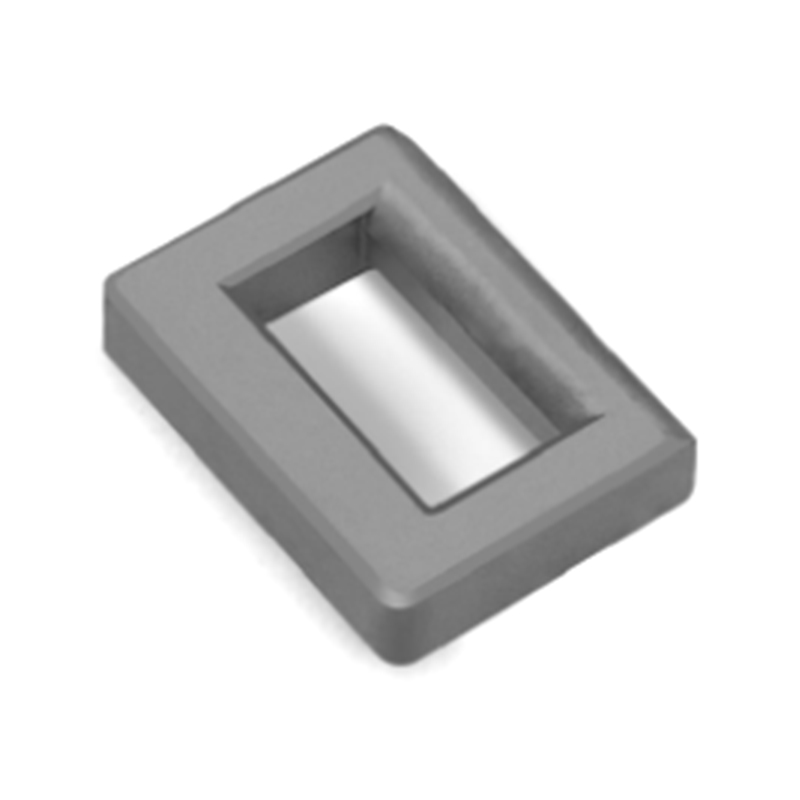

- Use core shapes with larger surface areas to improve convection.

- Select thermal interface materials when mounting cores inside enclosures.

- Design airflow paths or heat sinks for high‐power applications.

Evaluate the worst‐case operating temperature and derate core performance accordingly.

Common Challenges and Solutions

Engineers often face practical issues in MnZn ferrite core designs. This section outlines common challenges and actionable solutions.

Unexpected Core Saturation

If an inductor saturates prematurely:

- Increase core cross‐sectional area.

- Add an air gap to increase energy storage capacity.

- Reduce peak current or reassign turns.

Adjusting physical dimensions or topology often resolves saturation issues.

High EMI Emissions

Ferrite cores play a role in suppressing electromagnetic interference. If emissions remain high:

- Review winding layout to minimize loop area.

- Add or reposition common‑mode chokes.

- Consider shielded core geometries where appropriate.

Effective EMI mitigation often requires system‑level adjustments.

Conclusion: Maximizing MnZn Ferrite Core Performance

MnZn ferrite cores are indispensable in modern power electronics due to their high permeability and adaptable performance. Success in design and application demands careful selection of material grade, accurate analysis of inductance and loss, and rigorous thermal and mechanical considerations. By applying the principles outlined above, engineers can optimize core performance, reduce losses, and achieve reliable, efficient systems tailored to specific frequency and power requirements.

中文简体

中文简体